The heart of the Story Skills System is storytelling and character skills. It was designed to be a simple system where everything is a skill and, depending on your character and background, you can only be really good at some skills.

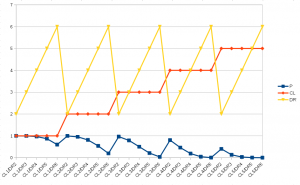

A task (something to which you are going to apply your skills) has one of 8 possible challenge levels (CL):

A task (something to which you are going to apply your skills) has one of 8 possible challenge levels (CL):

- Nominal

- Uncomplicated

- Challenging

- Difficult

- Hard

- Taxing

- Impossible

- Unthinkable

In addition, the task has a difficulty rate (DR). CL represents the number of wins you need to roll. DR determines how high the number needs to be to count as a win. The p-curve for those numbers is a tricky beast. Chances are, I’m going to have to reduce that to a table.

In addition, the task has a difficulty rate (DR). CL represents the number of wins you need to roll. DR determines how high the number needs to be to count as a win. The p-curve for those numbers is a tricky beast. Chances are, I’m going to have to reduce that to a table.

The relation of CL to DR is far from linear as I had initially assumed. As a rough rule of thumb CL plus DR is sort of equal to a factor that roughly expresses how hard something is. However, even that is a bit of a bumpy correlation. Trust me though, it’s a reasonable curve to play on.

Before we talk about skills we need to talk about transferable skills.

Transferable skills

The foundation of the story skills RPG system are your transferable skills. They express your strengths and weaknesses as a character. Due to being a stickler for realism, this was set up to ensure that there are areas your character is suited to and areas they will have to work much harder on to keep up.

From the (draft) core rulebook:

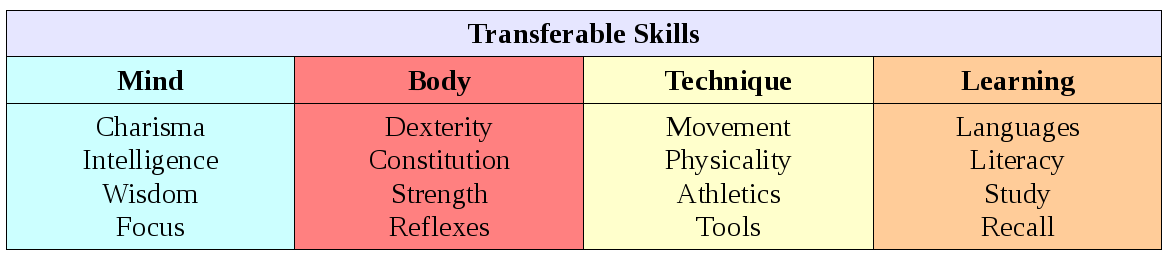

Transferable skills (TS) are your characters general strengths and weaknesses. They are grouped into four sets – Mind, Body, Technique, and Learning. Each character has one strong (Professional), two moderate (Competent), and a weak (Novice) TS set. These skill levels set the overall skill for all TS in the set. Additionally, you may have a number of points determined by your background to spend enhancing the individual skills in a given set.

As transferable skills (TS) are not usually tested directly they are not likely to change from one play session to the next. Transferable skills are the only skills not really subject to the “make it up as you go along” rule.

This is what the Transferable skills table looks like:

Skill dice pool (please don’t scream)

If you hate dice pools (and I know some players loath them) do not judge this book by your tatty old cover. This was the fairest random number generator with flexible upper limits possible without inventing a lot of new dice.

In this case, the dice pool just gives you some extra dice to throw at a problem.

You can tell very quickly how many dice you are rolling by looking at the dice you get four one of the four main groups (Mind, Body, Technique, and Learning), and the dice you get for the transferable skill that goes with the skill in question. These are your bonus dice. You can use as many of these (as you have available) up to the same number of dice you get from your skill’s proficiency. If you only get a D4 for the skill, you can only add another D4 from your pool. As long as you need a very small number of wins and a win is a fairly low number, you might be okay.

Now we can talk about skills

S3 Skills

Anything that your character can do is a skill. Magic, fighting, building, making, climbing… Whatever it is, it is a skill. Furthermore, there is no limit to the skills a character could conceivably have.

While it is true that there are some core skills (diplomacy, negotiation, perception, etc.) if your character concept is that they worked for ten years in the local fast food joint, your Narrator may agree that they have the skill Burger Flipping (Tools, Professional).

Role play over dice rolls

I strongly encourage you to not roll dice. Instead, you should roleplay the event out. If the task at hand seems like something that character would do easily, don’t roll for it, roll with it.

Should your character want to talk their way out of a difficult situation, that is not a diplomacy roll, that is an acting role. Dice are only for determining things that roleplay cannot determine.

Discovered skills

You do not need to have a fully formed character before you start playing. Like a discovery writer, you can learn about your character through play. For this reason, good roleplay should result in “discovering” new skills that the Narrator (GM) can award you. Picking up niche skills is a mark of a good player.

You do not need to have a fully formed character before you start playing. Like a discovery writer, you can learn about your character through play. For this reason, good roleplay should result in “discovering” new skills that the Narrator (GM) can award you. Picking up niche skills is a mark of a good player.

This is why introducing yourself as a character to the other characters is part of play. Not only are you getting to know your character, so are the other players.

This skills discovery mechanic is there to encourage playing a role rather than rolling a dice. Getting into character should lead to a much richer CV of available skills than simply reaching for your dice bag.

Reading a skill block

Okay, so block might be a bit of stretch but my grammar checker really wanted another word there. A skill is expressed in two parts – the name and the bit in brackets. The name is what the skill is. What that skill applies to is down to your Narrator and common sense. While the core rules and setting description may provide clarity the idea is that you should be able to play most games with nothing more than a single-sided character sheet and a few dice.

The bit in brackets should be fairly self-explanatory but I shall cover it anyway. A skill has a linked transferable skill. That’s what the skill is based on. Earlier, I made up the fast food skill Burger Flipping (Tools). That means you can add your tools TS dice to match your Burger Flipping skill dice.

The other word that you may seen in a skill description – yeah description is a far better word, I should use that – is the proficiency level.

I should probably cover those too.

Proficiency level

There are 8 levels of proficiency in any skill. Untrained is what everyone has in all skills. If you are untrained, don’t even bother writing that skill down, you don’t have it. You can try to use the skill (you get a D4 to play with) but unless the task is super easy, you are not going to get much satisfaction.

The proficiency levels are:

- Untrained

- Novice

- Amateur

- Competent

- Professional

- Expert

- Master

- Genius

The core rules explain how many dice these skills give you but to keep it simple, you get more dice the higher your level.

Skill progression

In the Story Skills RPG System, you progress through these levels as your character grows. However, there are special (story driven) rules for making the jump from competent to professional. The basic rule is that the advancement must make sense in story terms. Your Narrator is the ultimate arbiter of what counts.

In the Story Skills RPG System, you progress through these levels as your character grows. However, there are special (story driven) rules for making the jump from competent to professional. The basic rule is that the advancement must make sense in story terms. Your Narrator is the ultimate arbiter of what counts.

Progression costs points. You will start the game with some points which you can spend to set your character up with an initial set of skills. To get more points you need to use your skills. Solving a problem or advancing the story through role play or skill use nets you skill points. These might be rewarded for a specific skill (because you used it to solve the problem) or they might just float around for you to spend willy-nilly. Generally though, whatever you want to get better at – do that thing lots. Just like real life.

The cost of each proficiency level is fairly simple. “Untrained” is free – you’ve already got that covered. “Novice” is one point and “Amateur” is two. Each rank is, in fact, twice the cost of the previous one from “Amateur” onwards. If you get all the way to genius level you will have spent 127 points and your character will have an almost god-like grasp of the subject.

rewards for problem-solving and skill use will generally be of the order 1 to 4 points. You should only expect to get a lump sum of 4 points for something truly special or for reaching a significant story milestone.

This is what the draft rules say:

Any specific skill that a character achieves success with in an untrained skill check may make a second skill check at DR+1 to attempt to become novice. All further progressions require story driven rewards up to a maximum of competent. The Narrator may choose to allow you a point towards a skill for any given day wherein you roll one success in a skill where the CL was equal to or higher than the dice you have for your skill level.

Opposed skill checks

I’m not going to go into the details of it right now however when two characters (usually a PC and an NPC) are engaged in some sort of bluff and perception duel, or a fight, or whatever, this is an opposed skill check.

Generally, having a higher proficiency rating and/or some kind of situational or environmental advantage swings things in your favour. Luck is a factor but ability tends to trump luck more often than not.

This is the draft rules introduction:

Players should attempt to resolve conflict using improvisation (or character acting) in as far as possible. This will allow for the “discovery” of additional skills implicit in the character concept that the narrator can award the character. In this way, players are incentivised to play the role rather than just reach for the dice.

Maybe I’ll go into opposed skill checks in another post. Or maybe you can wait until the core rulebook is available. There are a few drafts doing the rounds if you happen to know the right people.

Conclusions and stuff

A long post like this feels like it should end with a conclusion. So I’ve started to write one.

In conclusion, play the role; don’t roll the dice. This game is fun. Play it.

Or something like that. I’ll write more soon (or I won’t).